Everlasting Beauty in the Pre-Raphaelites

Trendsetting has been a constant theme in the history of fashion and beauty. Take, for instance, the recent popularity of corsets in response to modern takes on period dramas such as Netflix’s Bridgerton and its most recent adaptation of Jane Austen’s Perception. Showcasing that in modern times, fashion culture is heavily derived from the arts and media of its time. Of course, for something to be set as a ‘trend’, it must first make a deep impression on its audience. Whether it be seen as outrageous or conventional for its time, something that was not unfamiliar to the soap opera of Pre-Raphaelite life...

Firstly, some background, the Pre-Raphaelite movement grew in the mid-19th century and gradually took the art world by storm. Their naturalistic view of the world broke away from Victorian austere portraiture and nurtured a softer and more mythical approach to art. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was formed in 1848, where a like-minded group of English poets, painters and art critics all contribute to the ‘aesthetics’ movement. Most notably, the Brotherhood included William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, from the Royal Academy in London. These men had a shared love for mythology and for medieval revivalism and worked to incorporate these classical motifs into their works. However, their quest to find and capture all things of beauty almost proved to be more of a burden.

Their new techniques used to promote romanticism were critiqued by the leading thinkers of the time such as Charles Dickens. Millais’ ‘Christ in the House of His Parents’ (1849–50) painting depicts the Holy Family working alongside the biblical St Joseph in his carpentry workshop. This was thought to be an obscene way of showing Christ in the Victorian times!

Ophelia by John Everett Millais (1851-52)

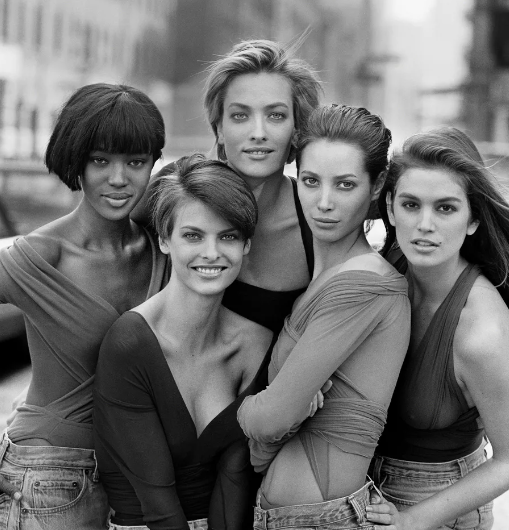

But these criticisms did not stop the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who continued to go against precedent and create these thought-provoking art pieces. It was not just the Brotherhood who were they only trendsetters in the Pre-Raphaelite movement, for their models provided them with both the beauty and much of the inspiration for their masterpieces. Rossetti would often call these women ‘stunners’ as they had delicate features that would work best to represent their idealised classical interpretations of age-old tales. The stunning Elisabeth Siddal was arguably the most famous of the Pre-Raphaelite models as she modelled for many of the paintings between the Brotherhood. She was described as having a magnificently tall figure, with fiery copper hair that made her the ideal muse for paintings. William Holman Hunt used her as his model for his painting ‘A Converted British Family Sheltering a Christian Missionary from the Persecution of the Druids’ (1849–1850). She was also the model for the famous rendition of Ophelia (1851-2) by Millais. She was tasked to sit in a bathtub to portray the drowning Ophelia, where in the winter months, she contracted severe pneumonia due to her sittings! Clearly, Pre-Raphaelite modelling was not a chore for the light- hearted. Yet, her endurance paid off, and the result, as I am sure you can agree, is simply breathtaking. You can visit this in the Tate Britain in London.

In the Brotherhood’s search for beauty, they focussed much on the naturalistic and everlasting beauty, typical of the Art Nouveau style. It is true that these women who possessed this type of beauty guided the artistic flares of the Brotherhood. Making these females, arguably the true revolutionaries who steered the movement into mainstream trends of the Victorian era. At this time, Victorian dresses were typically fastened tightly to hold a uniform silhouette, it was the standard that women of high standing would follow suit to fit in society. Corsets and crinolines were the undergarments used to perfect this look and many of the women incurred bruising from these usually insufferable binding clothes. Although much of the inspiration for these looks came from traditions in manipulating the image of women to appease the male gaze, it must be said that breaking these traditions in fashion also carried with it a new horizon for feminine beauty.

Elisabeth Siddal and Jane Morris, (who was the wife of textile designer and poet William Morris, also affiliated with the Brotherhood) adopted this change in costume, departing from the grandeur and fitted typical womenswear of the time. They were known to have either made or designed their own free-flowing and simplistic dresses that they promoted in Pre-Raphaelite art. Their bold choice of fashion vastly contrasted the precedents set in the mid-Victorian age. As shown in Siddal’s light and airy dress in Ophelia. With this representation in the arts, the Pre-Raphaelite women were able to express their own self-images and contribute to a changing Victorian visual culture.

Morris painted by Dante Gabriel Rossetti as Proserpine (1874)

Dante Gabriel Rossetti ensured that these ‘stunners’ were the focal piece of his work, often drawing and painting them with a particular gaze implying these women were deep in thought. The women of the Pre-Raphaelite movement greatly contradicted the typical Victorian women of the mid-19th century. As in England, women had limited rights over all their property and even less so when constricted within marriage. Pre-Raphaelite art, then and arguably now, represent the inner strength of women, forwarded by their natural beauty and elegance. Rossetti himself even married the model Elisabeth Siddal in 1860. Although it must be said that beauty’s true curse had captured these star-crossed lovers, as she died just two years after they wed, a suspected suicide that was kept under wraps to protect her and her family’s reputation. Rossetti, as both man and artist was fixated with everlasting beauty, and it was clear that he was easily led astray by all things beautiful, including many younger muses such as Jane Morris. After Siddal’s death, Morris became one of the main models for Rossetti and most likely engaged in an affair with her, despite her marriage to another brother.

In times of strict adherence to the rules, art tested and stretched many boundaries in both the fashion world and in high society. The women behind the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood steered much of this change in female Victorian fashion, yet their legacies of beauty in art and themselves proved instrumental to both their work as models and various entanglements within the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.